Have you bought or are you considering buying bitcoin or other cryptocurrency? And are you unsure of the rules regarding taxation? If the answer is yes, you are not alone. There are many reasons to be in doubt about the rules regarding the taxation of cryptocurrency – not the least being how these rules work in practice.

Have you bought or are you considering buying bitcoin or other cryptocurrency? And are you unsure of the rules regarding taxation? If the answer is yes, you are not alone. There are many reasons to be in doubt about the rules regarding the taxation of cryptocurrency – not the least being how these rules work in practice.

Samar Law is Denmark’s leading legal advisor in this area. Over the last several years, we have advised many companies and private persons on the taxation of cryptocurrency, as well as provided legal assistance in cases against the tax authorities. Our experiences are collected in this guide, which will be continually updated with new practice and new regulations.

Under Danish law, there is no special legislation which regulates the taxation of gains or losses from the sale of cryptocurrency, and over the years the statements of tax authorities on the topic have varied greatly, which has given rise to confusion. However, out of the practice of the last few years, guidelines have been developed, which has created a framework for the taxation of cryptocurrency. This guide collects the relevant legal rules and judgments and answers many of the questions we typically receive on the topic.

This guide is relevant for you, if you have bought or sold bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies or are contemplating buying or selling these as a private person. If you wish to read about the taxation of a company’s purchase and sale of cryptocurrency, keep an eye on this website and subscribe to our newsletter – an article regarding the taxation of a company’s purchase and sale of bitcoin is on the way.

**This guide is continually updated with new practice and guidelines – therefore this guide will always provide an overview of the current regulations – last updated the 25th of November 2020 **

1. WHAT DO THE RULES SAY?

Taxation regulation is structured so that The State Taxation Act regulates the taxation of assets, unless there is an additional special tax law regulating the taxation of the specific type of asset. Examples of these special laws are The Act on Taxation of Capital Gains on the Sale of Shares (aktieavancebeskatningsloven) and The Act on Taxation of Capital Gains on the Sale of Real Property (ejendomsavancebeskatningsloven), which regulate taxation of the profits from the sale of stocks and shares and real estate, respectively.

In a legal context, cryptocurrencies are still considered a new invention, which is not covered by any branch-specific regulations. Therefore, there is no special legislation, which regulates the taxation of cryptocurrency. Cryptocurrency is instead considered property on par with other unregulated types of property. This means that it is The State Taxation Act from 1922, which regulates the taxation of cryptocurrency.

2. WHAT IS A CRYPTOCURRENCY ANYWAY?

Most of the people who read this guide know what a cryptocurrency is. But does the law discriminate between a coin, a token, a stablecoin, a non-fungible token, etc.? And is there any difference in the taxation of these types of cryptocurrencies? A definition of cryptocurrency was only just introduced into Danish law in January of 2020, when the fifth Money Laundering Directive was implemented into the Money Laundering Act, where the definition of a cryptocurrency can now be found in § 2, no 15:

”A digital expression of value, which is not issued or guaranteed by a central bank or a public instance, is not necessarily attached to a legally established currency and does not possess a legal status of currency or money, but is accepted by natural or legal persons as a means of exchange and which can be transferred, stored and traded electronically.”

As it appears, the law does not differentiate between the different types of cryptocurrency. In practice, the tax authorities do not do an evaluation to determine whether or not a cryptocurrency is covered by this definition or not. This means that e.g. a bitcoin, which is a coin and ether, which is a token, are both taxed based on the same set of rules. With basis in the current practice, all cryprocurrencies are therefore taxed in the same manner, irrespective of the type of cryptocurrency. It is therefore not relevant if the cryptocurrency can be considered a coin, a token or something else entirely.

As it appears, the law does not differentiate between the different types of cryptocurrency. In practice, the tax authorities do not do an evaluation to determine whether or not a cryptocurrency is covered by this definition or not. This means that e.g. a bitcoin, which is a coin and ether, which is a token, are both taxed based on the same set of rules. With basis in the current practice, all cryprocurrencies are therefore taxed in the same manner, irrespective of the type of cryptocurrency. It is therefore not relevant if the cryptocurrency can be considered a coin, a token or something else entirely.

3. THE STATE TAXATION ACT – WHAT DOES IT SAY?

The rules on the taxation of cryptocurrency are found in The State Taxation Acts § 5, litra a. This means that realized gains from cryptocurrency are, as a main rule, not subject to taxation, and losses from cryptocurrency are not tax deductible.

So do you have to pay taxes on gains from cryptocurrency? You may have to, because there are two exceptions to the main rule. If one of these exceptions applies, gains from cryptocurrency are taxable and losses are deductible.

The first exception is if you acquired your cryptocurrency as a part of a for-profit business.

The second exception is if you acquired your cryptocurrency as a speculative investment.

For-profit businesses and speculative investments are defined in the following way in The Danish Tax Agency’s (Skattestyrelsen’s) Legal Guidelines (2-2020).

| Definition | The Legal Guidelines | |

|---|---|---|

| For-profit business |

A for-profit business is to be understood as the professional, comprehensive and systematic turnover of the specific type of asset, which occurs with the purpose of re-sale and with the goal of achieving an overall financial profit. However, it is also a requirement that the taxpayer has acquired or |

C.C.2.1.3.3.2 – link |

| Speculative investment |

The term speculative investment means that the specific asset must have been acquired with the goal of attaining a profit upon resale. Both the requirement of the intent to re-sell and the requirement that the re-sale |

C.C.2.1.3.3.3 – link |

More on what constitutes a for-profit business – when you e.g. live on the profits of your cryptocurrency

The literature on taxation states that the following factors must be included in an assessment of whether or not there is a for-profit business:

- The number and frequency of dispositions .

- The systematic and professional character of the dispositions.

- The suitability of the dispositions to return an economic profit.

- Are the dispositions business-economically grounded?

- The absolute and relative weight of the dispositions in the taxpayer’s economy.

- Outside financing of the dispositions through e.g. the taking out of loans, etc.

- The taxpayer’s educational and professional background for the activities performed.

The list of factors is non-exhaustive, as there a concrete assessment must always be done. The literature on taxation states that the number and force of the factors can vary from situation to situation and from asset type to asset type.1 This means that one factor can be assigned a determining weight in one case, while the same factor in another, dissimilar case can be assigned a lesser weight.

The current time there is not any practice in which the tax authorities have concluded that a person has acquired their cryptocurrency as part of a for-profit business. The Danish Tax Agency has handled cases involving people who have traded in cryptocurrency in systematic and comprehensive ways, at a profit and over a number of years, and yet have not found, that there was a for-profit business. Therefore, it must be assumed that the tax authorities are restrictive in regards to their assessment of whether or not a person has acquired cryptocurrency as part of a for-profit business.

More on what constitutes a speculative investment – if you have acquired cryptocurrency with the intent to re-sell them

The crucial issue in cases regarding the taxation of cryptocurrency is whether or not one has acquired their cryptocurrency as a speculative investment.

The deciding factor in the assessment of this question is whether or not there was an intent to re-sell, cf. the definition above as listed in The Legal Guidelines. As a main rule it is the intent at the time of acquisition, which determines whether or not one has acquired ones cryptocurrency as a speculative instrument. However, according to practice it is possible to trade ”out of” an intent to speculate, but it is never possible to ”trade in” an intent to speculate. This can be e.g. that the intent at the time of acquisition of the cryptocurrency was to invest these cryptocurrency in a ICO, but that one has since abandoned this idea and instead uses ones cryptocurrency for practical purposes, which after the assessment of the tax authorities is not considered speculation.

According to the practice of the tax authorities, the intent to re-sell does not necessarily have to be ”significant” at the time of acquisition.

The question of whether or not there was intent to re-sell is a subjective assessment. Therefore, the tax authorities have developed a practice, which includes a number of objective factors, which must be included in an assessment of whether or not there is speculation. This non-exhaustive list of factors can be presented in the following way. It must be noted that, as with the assessment of a for-profit business, there will always be a comprehensive, overall assessment which will be made, which is based on the actual concrete case:

- The time of acquisition – was it e.g. in connection with a special ”hype”?

- The purchasing sum – was the sum used to acquire e.g. high in relation to the person’s economic position?

- Pattern of trade – Did the person e.g. sell a short time after acquisition with a large profit and did they acquire a broad spectrum of cryptocurrencies, that have been traded back and forth?

- The purpose of the acquisition – was there e.g. a practical purpose for acquisition? This can e.g. be that one acquired ether with the purpose of using them as gas or a token in order to use their utility value or governance function in a blockchain-based game or similar?

- The person’s background and academic interest in cryptocurrency – is this e.g. a person, who is actually or ideologically interested in cryptocurrency?

4. WHAT IF I AM LIABLE FOR TAXES?

If it is concluded that you have acquired your cryptocurrency as either a speculative investment or as part of a for-profit business, the realized gains of your cryptocurrency is taxable, and you can likewise deduct the realized losses of your cryptocurrency.

Gains are taxed as normal salary income, which can be up to top-bracket tax, equal to approximately 56 %.2 Losses trigger a tax deduction (personal relief) equal to approximately 30 % (2020).

Gains must be reported on the annual tax return under heading 20, and deductions must be reported under heading 58.

Because there is a difference between the percentage of taxes payable on gains and the percentage of losses that are deductible, the term asymmetric taxation applies. Additionally, the calculation of taxes must be done after the principle of realization (and therefore not after the stock principle). According to the practice of the tax authorities, realization occurs each time the specific cryptocurrency is exchanged – regardless if it is exchanged for another cryptocurrency, fiat currency or another object of value. This means, among other things, that each trade is taxable. This is something that often surprises our clients, and it can be illustrated with the following example:

Example 1:

Person A bought 1 bitcoin for 1,000 DKK via en exchange on the 1st of January.

After this, Person A exchanged 1/2 bitcoin for 100 ether at a rate of 10 DKK/ETH.

That is to say, that the 100 ether, at the time of exchange, had a value of 1,000 DKK.

Person A has therefore achieved a gain of 500 DKK, that they must pay taxes on in accordance with the realization principle as described below.

It is also important to point out, that gain and losses are calculated continually at the time that the cryptocurrency is traded. This is the opposite of how cryptocurrency is taxed in many other countries, where the taxation first occurs when one transfers fiat currency to one’s bank account.

Asymmetrical taxation combined with the realization principle can in many cases result in a taxation level of over 100 %. An example of this can be illustrated in the following way:

Example 1:

Person A owns 1 bitcoin.

A sells half of their bitcoin and makes a profit of 110 DDK.

Later, A sells the other half of their bitcoin, occurring a loss of 100 DKK.

A has therefore earned a profit of 10 DKK.

However A must pay approx. 55 DKK in tax and can deduct 30 DKK.

A’s total taxation is therefore 25 DKK, which is equal to a tax rate of 250%.

Example 2:

Person A owns 1 bitcoin.

A sells half of their bitcoin and makes a profit of 50 DKK.

Later, A sells the other half of their bitcoin, occurring a loss of 80 DKK.

A has therefore lost a total of 30 DKK.

However A must pay approx. 25 DKK in tax and can deduct 10 DKK.

A’s total taxation is therefore 15 DKK, even though A has lost 30 DKK.

5. DEDUCTION – A PERSONAL RELIEF DEDUCTION?

SKM2018.104.SR was the first decision, in which the tax authorities decided that a realized loss from cryptocurrency should be classified as giving a personal relief deduction. This can be attributed to a decision made by the Tax Council (Skatterådet), which concluded that losses occurred from speculation were not covered by the deduction rules found in The Personal Income Tax Act § 3 (2) or of The Personal Income Tax Act § 4.

However, legal literature expresses doubt regarding this decision. This is due to the fact that the Tax Council only assessed whether or not the above named statutes in the Personal Income Tax Act could be used. The Tax Council did not assess, whether a loss was covered by The Personal Income Tax § 3 (1), of which some particular circumstances point to.

If a loss were covered by the Personal Income Tax Act § 3 (1), a taxpayer would have the right to calculate the net amount of their gains and losses. In practice, this would mean that a taxpayer would be taxed for their actual gains and thereby not risk taxation rate of over 100 %. However, the question has yet to be answered by the tax authorities. Keep an eye on this website, as an article on this specific topic is on the way.

6. THE TAXATION CALCULATION

The Tax Council has published a number of decisions regarding the taxation of cryptocurrencies. There are two primary decisions on this matter, which have been published as SKM2018.104.SR and SKM2019.67.SR, which will be summarized separately below.

SKM2018.104.SR – the first case before the Tax Council on bitcoin and tax

SKM2018.104.SR, as named above, was the first case in which the Tax Council made a decision regarding the calculation of taxes with the relinquishment of cryptocurrencies.

In the case, the Tax Council found, with reference to the State Taxation Act § 5, litra a, that losses and gains must be calculated separately for each relinquishment and on the background of the difference between the actual acquisition sum and the relinquishment sum for the particular cryptocurrency. This principle is called the ”asset-for-asset” principle.

The asset-for asset principle

In relation to partial relinquishment (e.g. relinquishment, where the entire holding of virtual currency is not relinquished at one time), the Tax Council has specified, with the above mentioned as a starting point, that the State Taxation Act § 5, litra a, does not regulate ”a calculation method for partial relinquishment from a holding of uniform or not specifically identified goods of value, which are acquired for the purpose of speculation”.

On that background, the Tax Council found that when it was not possible to identify the relinquished virtual currency in cases of partial relinquishment, and the acquisition sum, as a result of this, could not be calculated, the acquisition sum for the first acquired bitcoins should be used in the calculation of gains or losses with every partial relinquishment. This principle is called FIFO (First In First Out).

The FIFO-principle (First In First Out)

The determining factor for whether or not the FIFO principle should be used is whether or not the relinquished cryptocurrency can be identified, including whether or not the precise acquisition sum for these can be identified. Where this question can be answered positively, the asset-to asset principle should be used, and in the opposite case, the FIFO principle should be used.

The decision states the following regarding this problem:

“It is the Tax Authority’s understanding that The FIFO principle should cover an aggregation of all of the taxpayer’s holding of bitcoins, when these are found in multiple accounts or wallets.

In other cases, where there is no identification problem, e.g. where all bitcoins are relinquished at the same time, even if these are divided between multiple accounts or wallets, the calculation of gains or losses is to be made on the basis of the difference between the sales sum and the actual acquisition sum for the sold bitcoins” (our underlining)

It was therefore the opinion of the Tax Council that in light of the State Taxation Act § 5, litra a, that the applicable main rule is that the asset-to-asset principle should be used. The exception to this is the circumstance where a partial relinquishment of a holding of cryptocurrency takes place, where the cryptocurrency is not individually identifiable. In such a case, the FIFO-principle is used. This was confirmed in SKM2018.130.SR.

SKM2019.67.SR – on the rules for tax related calculation of cryptocurrency.

In SKM.2019.67.SR, the Tax Council explained the principles of calculation in SKM.2018.104.SR and elaborated on under which circumstances the two calculation principles are to be used.

The Tax Council laid out the following in relation to this dilemma:

“The Tax Council cannot deny, that today or in the future, methods can be found which could make it possible to individual bitcoins, which would make it possible to determine which bitcoins have been removed from a holding through partial relinquishment. Whether or not a secure identification can occur is dependent on a concrete evidentiary evaluation of the documents presented. As this documentation is not presented in this particular case, the Tax Council cannot make a concrete evaluation of the Applicant’s dispositions. In the event that the Applicant can present such a method, the FIFO principle, in the Tax Council’s opinion, is not applicable. In such a case the main rule will be that the asset-for-asset principle in the State Taxation Act § 5 (1), litra a, is the applicable rule.”

It can thus be seen that the Tax Council, with the citation above, confirms the legal status which was laid out in SKM.2018.104.SR, cf. above.

To show how this calculation method must be used in practice, we have made a couple of examples:

Example 1:

A buys 1 bitcoin for 1,000 DKK the 1st of January.

A buys 1 bitcoin more for 2,000 DKK the 1st of February.

Both bitcoins are stored in the same wallet X.

A sells ½ of a bitcoin for 1,000 DKK on the 1st of March from wallet X.

Because it is not possible to identify whether the half bitcoin, which A sold the 1st of March, comes from the acquisition of a bitcoin on the 1st of January or from the 1st of February, it is not possible to determine the price at which A acquired the half bitcoin. Therefore, the FIFO principle applies.

A must therefore make their tax calculation based on the first acquisition on the 1st of January. As a consequence, A must be taxed for a profit and 500 DKK.

Example 2:

A buys 1 bitcoin for 1,000 DKK the 1st of January.

A buys 1 bitcoin more for 2,000 DKK the 1st of February.

A’s bitcoins are now stored in two different wallets – wallet X and wallet Y.

A sells ½ a bitcoin for 1,000 DKK on the 1st of March from wallet Y.

Because it can be identified, that the ½ bitcoin comes from A’s acquisition on the 1st of February, the price of acquisition can also be determined. Therefore, the asset-to-asset principle applies.

A must therefore make their tax calculation based on the acquisition made on the 1st of February. A has therefore not occurred any gains or losses and is for that reason not liable for taxes regarding this relinquishment.

This example illustrates, why it is important to analyze which of the calculation principles are applicable. If one were to use the FIFO-principle, one would mistakenly come to be taxed for on the basis of 1,000 DKK.

7. BITCOIN RECEIVED AS A GIFT

The tax authorities have in a specific case decided how to calculate tax on bitcoin received as a gift. The decision is published as SKM2019.78.SR.

The case regarded a taxpayer, who had received two bitcoins from their romantic partner as a Christmas gift in 2013.

In the case, the Tax Council decided that the taxpayer could realize their bitcoins tax free, as these were received as a gift. The fact that the taxpayer had not wished for the bitcoins as a gift, and that besides the gift-giver, there were other people who were witness to the transfer, were mentioned in the decision.

It is not described in the decision, whether or not the tax authorities used any of these factors in their evaluation or simply mentioned them as circumstances of the case. It is our experience from other similar cases that the Danish Tax Agency makes an intensive evaluation of whether or not the specific cryptocurrency was actually given as a gift.

8. HARD FORK AND AIRDROP

Certain situations can arise, where the owner of a specific cryptocurrency receives new cryptocurrency due to the fact that they are already in possession of that particular type of cryptocurrency. That is to say, that the owner does not actively do anything in order to receive the new cryptocurrency. In practice this is called a hardfork or an airdrop. It is important to be aware that the tax treatment of hardforks, airdrops and also staking under the circumstances is different compared to regular trading with virtual currencies.

Hardfork – splitting of an existing blockchain

For a public blockchain to function, it is a requirement that there is consensus among the nodes on the blockchain regarding the rules of the specific blockchain, including the way in which the new blocks on the blockchain are generated and the way transactions are verified.

Historically, there have been some situations, where there has not been a consensus between the nodes. This has resulted in the creation of a new, independent blockchain with it’s own rules and it’s own new, independent virtual currency, and a continuation of the original blockchain, which continues to use the original rules.

This situation, in which a new independent blockchain is created with a new, independent virtual currency, is called a hardfork.

When a hardfork occurs, the owners of the virtual currency, which belongs to the original blockchain, receive – without any form of payment – an equal amount of the virtual currency belonging to the new blockchain. Examples of hardforks that already have happened are bitcoin cash and ethereum classic, which were ”forked” out of bitcoin and ethereum, respectively.

The tax authorities have, in a decision published as SKM2018.104.SR, made a concrete determination regarding how hardforks should be treated in a tax context. The case regarded how, in tax context, to treat bitcoin cash, which a taxpayer had received as a result of the hardfork to the Bitcoin blockchain. The Tax Council remarked as such:

”It is TAX’s opinion, that the award of bitcoin cash is tax free for the applicant at the time of the award, because the award must be assumed to be a result of the previously purchased bitcoins and therefore also acquired with the same intent.

This means, that taxation of bitcoin cash first taxes place at the time of relinquishment, cf. the State Taxation Act § 5 (1), litra a.” (Our underlining)

Therefore, it can be concluded that the cryptocurrencies one is awarded in connection with a hardfork, are to be treated the same way as the cryptocurrencies, which they are hardforked ”out of”. In the particular case this is to say that the specific taxpayer is not liable for taxes on the realized gains achieved from bitcoin cash, under the presumption that he is also not liable for taxes on the gains achieved from bitcoin.

As long as one is liable for taxes on the realized gains of the cryptocurrencies which one has been awarded in connection with a hardfork, the tax calculation shall be made with the starting point of a acquisition sum of 0 DKK.

Airdrop – an award of new cryptocurrencies

An airdrop occurs when the persons behind a specific cryptocurrency award this cryptocurrency to – most often – all wallets, which already contain another type of cryptocurrency. This can e.g. happen, if the people behind cryptocurrency A decide to award 10 of cryptocurrency A to all who already are in possession of cryptocurrency B.

An airdrop typically is done as for promotional reasons, as they typically involve new types of cryptocurrency.

The tax authorities have not yet published any practice in which they take a stance on the tax specific treatment of cryptocurrencies received as the result of an airdrop. Because the purpose of an airdrop is typically promotional, because the awarded cryptocurrency is given to a (very) wide group of people, and because the cryptocurrency typically has a very low value at the time it is awarded, it is our opinion that these are promotional gifts, which are covered by the State Taxation Act § 4. In such a case, one is liable for taxes on the value of the awarded cryptocurrency at the time the award is given, if that value is not minimal, whilst a later increase in value will not have an effect on the calculation of one’s income.

In practice it is very difficult to determine whether or not the value is minimal. This is due to the particular cryptocurrency being in an establishment phase, where they are not yet traded on the established market. Therefore it is very difficult to determine the cryptocurrency’s market price and as a result, difficult to determine whether the value is minimal or not.

9. FINANCIAL CONTRACTS

As named above, cryptocurrencies are, in a tax context, considered to be an object of value and must therefore be treated according to the rules in the State Taxation Act.

Dependent on a variety of factors, a trade with cryptocurrency can be considered to be a financial contract, which must be treated tax-wise as such, cf. (among others) SKM2018.130.SR.

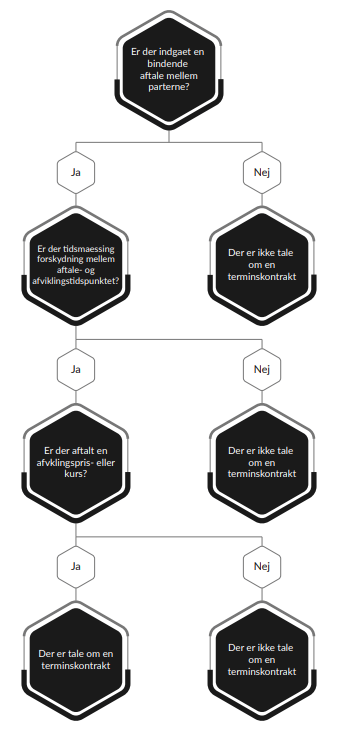

Financial contracts are regulated in the Act on Capital Gains Tax on the Sale of Receivables, Debt and Financial Contracts (kursgevinstloven) § 29 (1). This statue specifies that three requirements must be fulfilled before a contract can be considered a financial contract:

1. Two parties must have entered into a binding agreement with each other.

2. There must be a chronological displacement between the time of agreement and the time at which the agreement is settled.

3. There must be an agreement on the settlement price or settlement index.

These are cumulative requirements, all of which must be satisfied, before a contract can be considered a financial contract after the Act on Capital Gains Tax on the Sale of Receivables, Debt and Financial Contracts (kursgevinstloven) § 29 (1).

The following decision tree can be used to determine whether or not there is a financial contract.

10. DOCUMENTATION IN CONNECTION WITH LOSSES

The Danish Tax Agency (Skattestyrrelsen) can always challenge tax assessments. That is to say, that the Danish Tax Agency can always evaluate, whether the information provided by a company in connection with its trade of cryptocurrencies is correct.

In connection with this, we have experience regarding the type of documentation, which the Danish Tax Agency typically requests. This is especially relevant in the case of losses. It must be noted, that there is a high probability of a deduction being permitted, even though one cannot provide all of the documentation, which the Danish Tax Agency requests.

The Danish Tax Agency typically requests documentation of the following:

-

A calculation of the gains and losses, calculated after the FIFO principle for every sale, divided by income year.

-

Information regarding the intent behind the acquisition of cryptocurrencies.

-

Documentation of the creation of wallets.

-

Documentation of the creation of a user profile on a crypto-exchange as well as the exchanges terms and conditions.

-

An overview of transactions from all crypto-exchanges as well as of the continual holding of cryptocurrencies (note that on most crypto-exchanges, a .csv file containing this information can be downloaded).

11. THE TAXATION OF BITCOINS IN CONNECTION WITH MOVING AWAY FROM DENMARK

We often receive questions from Danes, who for the purpose of tax optimization, wish to move away from Denmark to another country with more relaxed taxation of cryptocurrency.

The tax calculation of cryptocurrency in connection with moving away from Denmark is regulated in The Danish Withholding of Tax Act (kildeskatteloven) § 10 (1) (also referred to as ”exit-taxation” or ”Garden gate taxation”).

First and foremost, it must be noted that the applicability of the rules require that one has moved away from Denmark at therefore given up one’s full tax liability to Denmark in accordance with The Danish Withholding of Tax Act § 10 (1), no. 1 (”the global income principle”). The requirements for this will not be discussed further in this guide, but it is noted that the tax authorities have a relatively restrictive practice in relation to this question.

As long as a person has moved away from Denmark and given up their full tax liability in the country, it follows of the rules in The Danish Withholding of Tax Act § 10 (1), that ”assets, which are no longer subject to Danish taxation, are [considered] relinquished at the time of moving. The assets are considered to have been relinquished for market value at the time of moving.”

In practice this means that cryptocurrency is considered to have been realized in connection with moving. As a rule, it is possible to get respite from payment of the calculated taxes.

The rules regarding moving can be illustrated by the examples below. For both examples, it is assumed that A acquired their bitcoin with the intent of speculation.

Example 1:

A buys 1 bitcoin for 1,000 DKK on the 1st of January 2020.

A moves away from Denmark the 1st of February 2020, and in connection with this gives up their full tax liability to Denmark.

The market value of 1 bitcoin is 2,000 DKK at the time of moving.

A is therefore taxed for a gain of 1,000 DKK at the time of moving.

Example 2:

A buys 1 bitcoin for 1,000 DKK on the 1st of January 2020.

A moves away from Denmark the 1st of February 2020, and in connection with this gives up their full tax liability to Denmark.

The market value of 1 bitcoin is 500 DKK at the time of moving.

A gets the right to deduct their loss of 500 DKK at the time of moving.

Example 3:

A has now lived in another country for many years and wishes to move back to Denmark.

On the 1st of January 2030, A moves back to Denmark, and in connection herewith becomes fully tax liable to Denmark once again.

The market value of 1 bitcoin is 100,000 DKK on the 1st of January 2030.

On the 1st of February 2030, A sells their bitcoin for 101,000 DKK.

It is the value at the time of A’s moving back to Denmark, which is seen as A’s acquisition sum.

A is therefore taxed for a gain of 1,000 DKK.

12. WHAT HAPPENS, IF I LOOSE MY CRYPTOCURRENCY?

It is commonly known that cryptocurrencies were created to have a decentralized nature, where after the person, which is in possession of the private key connected to a specific wallet, also has access to this. If a person looses their private key, they also loose access to their cryptocurrency. There is no central authority, from which one can appeal to in order to re-generate one’s wallet, and as a main rule, the loss of one’s wallet is permanent – and one’s cryptocurrency is permanently lost with it.

We often receive inquiries from people, who have lost their telephone or computer, where their private keys were placed. It can also be that they have lost their ”master seed” to their hardwallet, or that a cryptocurrency exchange has been hacked.

But how should this be handled legally? Is there a loss, which can be deducted in taxes?

The State Taxation Act § 5 cannot be applied as a basis in law for a deduction. Therefore, the question is, whether or not Act on Capital Gains Tax on the Sale of Receivables, Debt and Financial Contracts (kursgevinstloven) § 14 is applicable to the loss. This question was answered in SKM2018.104.SR, where the Tax Council stated:

”In this context it should be noted, that losses which are occurred as a result of lost codes to a virtual wallet are, after TAX’S opinion, not losses which are tax deductible.

This is partially due to the fact that the contents of the virtual wallet are not lost, meaning that the ownership is still extant, and partially that the tax specific loss deduction on goods of value acquired with the intent of speculation requires that the specific goods have actually been traded/sold.”

As shown, the tax authorities place a deciding weight on the fact that the lost private key consists of a lost access to one’s cryptocurrency and not a loss of the cryptocurrency itself. Based on the assumption that one still has the legal ownership of the specific cryptocurrencies, it has been evaluated that a deductible loss has not occurred. This concept appears to be very theoretical, as a permanent loss of a private key consists of a de-facto permanent loss of a holding of cryptocurrencies.

Additionally, through the practice of the tax authorities, a concept has emerged, which entails that there must be an identifiable debtor as a requirement for a loss to be tax deductible after Act on Capital Gains Tax on the Sale of Receivables, Debt and Financial Contracts § 14. In relation to cryptocurrencies, this creates a de-facto legal status, where after it is not possible to attain a right to deduct the loss of lost cryptocurrencies, but alone possible to deduct the loss of stolen cryptocurrencies.

The concepts described above have been criticized in the legal literature and it is possible that the tax authorities may, in time, reach a different conclusion through the evaluation of specific cases.

***

Do you find there are any areas not covered by this guide? Or do you have any questions, which you would like our help with? If so, send a mail to Attorney payam@samarlaw.dk or give him a call at 60793777.